In Part I, How the World Became Flat, Friedman visits India, where

he realizes that the playing field has been leveled, meaning that a much

larger group of people can compete for global knowledge. He pursues examples

of this metaphor in other places, such as Iraq, China, Japan, and the

United States. Friedman argues that there are primarily ten forces that

flattened the world and describes each of the following flatteners:

11/9/89, the fall of the Berlin Wall; 8/9/95, or the date that Netscape

went public; work flow software; uploading; outsourcing; offshoring; insourcing;

in-forming; and the steroids. Next Friedman explores what he calls the

triple convergence, or the way the ten flatteners converged to create

an even flatter global playing field. The first convergence encompasses

how the ten flatteners came together in such a way that they created a

global, Web-enabled platform that allows for multiple forms of collaboration.

The second convergence is the appearance of a set of business practices

and skills that make the most of the ten flatteners, thus enhancing the

flatteners' potential. The third convergence is the entrance of some three

billion people onto the playing field. The triple convergence is likely

to cause some chaos and confusion. Friedman argues that the great sorting

out will recalibrate the ceilings, walls, and floors that define us.

Some questions that arise during the great sorting out are: what should

be the relationship between companies and the communities in which they

operate?; how do we navigate our multiple identities as consumers, employees,

citizens, taxpayers, and shareholders?; who owns what, particularly in

the case of intellectual property?

In Part II, America and the Flat World, Friedman begins by claiming

that free trade is still in the United States' best interest because as

long as the global pie keeps growing--that is, as long as more people

demand these goods and services, more people will be needed to produce

them. Friedman points out that the Chinese and Indians are racing Americans

to the top, not to the bottom. This race will foster higher standards

for everyone. Friedman shows how, as services and goods become increasingly

tradable, more jobs are likely to become outsourced, digitized, or automated.

He predicts that untouchable jobs in the new flat world will fall into

three, broad categories: people who are special or specialized (e.g.

Madonna, Michael Jordan, or your brain surgeon); people who are localized

and anchored (e.g. waitresses, lawyers, plumbers, nurses, etc.); and

the old middle jobs (e.g. people in the middle class who are under pressure

because their jobs are becoming tradable). Friedman explores what he thinks

the new middle-class jobs will be in the flat world, calling the people

who will occupy those jobs--which he divides into eight categories-- the

new middlers.

The eight categories are: Great Collaborators and Orchestrators, The

Great Synthesizers, The Great Explainers, The Great Leveragers, The

Great Adapters, The Green People, The Passionate Personalizers, and

The Great Localizers. Friedman outlines four skill sets and attitudes

that educators and employers point to as the right stuff to make it

in the flat world. The first skill set individuals must possess is the

ability to learn how to learn. The second skill set is what Friedman

dubs CQ + PQ > IQ, or that curiosity and passion, combined, are more

important than intelligence. The third skill set/ attitude Friedman uncovers

is Plays Well with Others. The final skill set Friedman believes will

be necessary in the flat world is The Right Brain Stuff. Friedman believes

that the United States is uniquely suited to enter the age of the flat

world because it has a mix of institutions, laws, and cultural norms

that produce a level of trust, innovation, and collaboration that has

enabled us to constantly renew our economy and raise our standard of living.

The problem, it seems, is that Americans are not taking advantage of their

nation's potential.

Friedman unveils six dirty little secrets, which help explain why Americans

are not taking advantage of these resources and what will happen if they

do not change course. The dirty little secrets are: The Numbers Gap,

The Education Gap at the Top, The Ambition Gap, The Education Gap

at the Bottom, The Funding Gap, The Infrastructure Gap. Next Friedman

outlines the five action areas of compassionate flatism, which is what

he believes it means to be progressive in a flat world. The goal of compassionate

flatism is to reconfigure the old welfare state to give Americans the

outlook, education, skills, and safety nets they will need to compete

against other individuals in the flat world. The five action areas are:

leadership, muscles, good fat, social activism, and parenting.

In Part III, Developing Countries and the Flat World, Friedman considers

what policies developing countries must carry out to thrive in the flattening

world. These steps include: introspection, commitment to more open and

competitive markets, and the cultivation of infrastructure, education,

and governance, as well as the creation of business-friendly environments.

Friedman then offers Ireland as an example of a nation that went from

the sick man of Europe to the rich man by addressing these issues. Friedman

believes that to truly understand a country's economic performance, one

must also consider its culture. Friedman argues that open cultures, which

are best able to adopt global best practices and willing to change--versus

closed cultures, which promote tradition and national solidarity--have

the best chance for success in the flat world. Finally, Friedman observes

that even when nations get it right--reform wholesale, reform retail,

maintain good governance, infrastructure, and education, as well as glocalize--some

proceed in a sustained manner while others do not. Friedman calls the

missing element the intangible things. Friedman boils the intangibles

down to two basic elements: a willing society and leaders with vision.

Friedman provides a comparison between Mexico and China to show how Mexico

failed and China succeeded.

In Part IV, Companies and the Flat World, Friedman imparts an observation

he has made while researching this book, which is that the companies

that have managed to grow today are those that are most prepared to change.

Friedman shares seven rules he has learned from these companies. Rule

#1 is When the world goes flat --and you are feeling flattened-- reach

for a shovel and dig inside yourself. Don't try to build walls. Rule

#2 is And the small shall act big... Rule #3 is And the big shall act

small... Rule #4 is The best companies are the best collaborators.

Rule #5 is that In a flat world, the best companies stay healthy by getting

regular chest X-rays and then selling the results to their clients. Rule

#6 is that the best companies outsource to win, not to shrink. Rule

#7 is that Outsourcing isn't just for Benedict Arnolds. It's also for

idealists.

In Part V, Geopolitics and the Flat World, Friedman explores some

of the reasons why flattening could go wrong. He sets out to answer the

following questions: What are the biggest constituencies, forces, or

problems impeding this flattening process, and how might we collaborate

better to overcome them? The groups of people for whom the world might

not flatten are comprised of those who are too sick, too disempowered,

and the too frustrated. Friedman notes that if the many people that

live in the unflat world enter the flat world (as they are beginning to

do) there will be an environmental crisis. He urges Americans to take

seriously the damage they are wreaking on the environment through their

waste. He believes it is in the U.S.'s best interest to collaborate with

China and India to reduce energy consumption. In becoming the Axis of

Energy these nations could effectively disempower the Axis of Evil.

Friedman also considers the surprising, important, and paradoxical effects

flattening is having on culture around the world. Initially, Friedman

says, there was concern that globalization was really Americanization

in the form of American cultural imperialism. This is because American

cultural products (films, music, chain restaurants, etc.) were in the

best position to take advantage of the flattening of the world. However,

Friedman believes that while the flat world platform has the potential

to homogenize cultures, it has a greater potential to foster diversity

to a greater degree than has ever happened before. The primary reason

for Friedman's outlook is uploading's capacity to globalize the local.

That is, because anyone with access to a computer and the Internet can

put content on the Web, local culture can be spread globally. Friedman

is aware that there are also negative aspects of flattening's effects

on culture. He notes that the potential is just as great for criminal

groups to come together in this smaller world as it is for progressive

groups and mentions the pedophiles that paid Justin Berry to perform sexual

acts in from of a web-cam for several years. Friedman establishes The

Dell Theory of Conflict Prevention based on Dell's Asian supply chain,

arguing that nations deeply invested in just-in-time global supply chains

are much less likely to engage in war than they were previously (old-time),

because they will withstand significant financial losses. This is relevant

to Friedman's larger arguments about the flat world because Friedman contends

that war substantially slows (or stops) flattening. According to Friedman's

theory, countries such as Japan, South Korea, China, Taiwan, Malaysia,

Singapore, the Philippians, Thailand, and Indonesia can work together

and resist war, despite political or cultural differences, because they

are all economically invested in a supply chain. Conversely, nations such

as Iraq, Syria, south Lebanon, North Korea, Pakistan, Afghanistan, and

Iran are not part of any major global supply chains and, therefore, remain

hot spots because they will not suffer similar economic set backs due

to war. Friedman notes that supply chains are not always good. The technology

that enables countries to become more competitive and economically secure

also enables terrorist organizations, such as al-Qaeda or suicide bombers

in Iraq. Friedman reminds the reader that Osama bin Laden did not use

nuclear weapons on 9/11 because he did not have the capability, not because

he did not have the desire. Friedman argues that the best way we can combat

suicide supply chains is by limiting the supply of nuclear weapons.

|

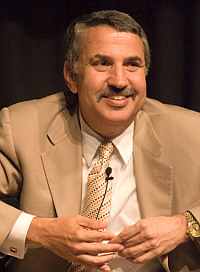

Thomas L. Friedman |

In Part VI, Conclusion: Imagination, Friedman emphasizes the competing forms

of imagination at work in the world today, which are seen in the differences

of 11/9 (the day the Berlin Wall came down) and 9/11. For Friedman, 11/9

represented a more open world. 9/11, conversely, demonstrated how evil

imaginations could close the world up. Friedman unfurls how the plans

for 9/11, as elaborated in the 9/11 Commission Report,

were similar to many business ventures, with Khalid Sheikh Mohammed

the eager engineer-entrepreneur and Osama bin Laden the wealthy venture

capitalist. Friedman argues that technology such as iris scans and x-ray

machines will help thwart those who are trying to destroy the flat world,

but technology alone will not keep us safe. Additionally, we must affect

the imaginations of those who would use the tools of the flat world to

terrorize others. Friedman closes with an anecdote about dropping off

his oldest daughter, Orly, at college in the fall of 2004. This was one

of the saddest days in Friedman's life, not only because his daughter

was growing up, but because he felt this world was so much more dangerous

than the one she was born into.

Thomas L. Friedman - BIOGRAPHY

Thomas Friedman was born in St. Louis Park, Minnesota on July 20, 1953. He graduated in 1975 from Brandeis University with a Bachelor's degree in Mediterranean Studies. In 1978, Friedman received a Master's degree from Oxford University in Modern Middle East studies. Friedman began working as a correspondent for the New York Times in 1981 and spent many years reporting from Israel. Friedman was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 1983 and 1988 for international reporting. In 2002, Friedman received a third Pulitzer for commentary. Thomas Friedman is married and has two daughters.

Selected Works:

From Beirut to Jerusalem, 1989

The Lexus and the Olive Tree, 1999

Longitudes and Attitudes: Exploring the World After September 11, 2002

The World Is Flat: A Brief History Of The Twenty-first Century, 2005

The World Is Flat: A Brief History Of The Twenty-first Century, The

Updated and Expanded Version, 2006

GENRE

Non-Fiction

Clapsaddle, Diane. "TheBestNotes on A Long Way Gone".

TheBestNotes.com.

>.